African Memoirs: Black Internationalism

Struggles, Strategies, and Successes in Global Perspective

Sarah–Jane (Saje) Mathieu – University of Minnesota

From the end of the nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth century black activists across the Atlantic world showcased their transnational political savoir faire, demonstrating how African-descended peoples profited from thinking and acting globally. For example, African Americans, especially scholars, entertainers, athletes, soldiers, and missionaries, traveled extensively, embracing new ideas, new strategies, and new solutions that they then applied back in the United States. As an illustration, Paul Robeson told reporters that his time in fascist Spain during the 1930s made all the more urgent his civil rights work in the United States.

Thus, the various types of transnational alliances and international black organizations formed during the "Africana Age" showcase the broad scope of political ideologies that appealed to African Americans, Africans, and Caribbeans desperate for new ways of navigating the challenges presented by white supremacy.

Emigration and Migration

Emancipation in 1865 signaled an era of great hope for African Americans. With the advent of Reconstruction, they contemplated the meaning of their new freedom and debated their next moves: migrating, reuniting with their families, securing waged work, purchasing land, learning how to read, and pursuing a more extensive education. Even against the background of tremendous political reform, some black intellectuals like Reverend Edward W. Blyden proposed that blacks consider leaving the United States, given the rising tide of violence perpetrated by white supremacist groups like the White Knights, the Regulators, and the more readily recognized Ku Klux Klan. Blyden and others advocating a return to Africa pointed to the unlikelihood that African Americans would ever enjoy meaningful citizenship in the United States.

Meanwhile, Dr. Martin Delany, a Harvard-educated physician, stressed that Africa urgently needed American industry and that Africans could also profit from Christian missionary work. Thus, the early appeal for emigration to Africa came from prominent African-American ecclesiastic leaders, with Henry McNeal Turner, Martin Delany, and Alexander Crummell perhaps the best known among their peers, and African-American missionaries set up some of the earliest black utopian Christian emigration societies in western and southern Africa during the late nineteenth century, wedding American modernity with African cultures.

Eager for a safe haven from the culture of violence spreading throughout the South thanks in large part to white supremacist organizations, many African Americans quickly sold their land and other possessions before making their way to eastern port cities and boarding ships to western Africa. In 1877, for example, rumor quickly spread in Arkansas that African Americans were leaving for Africa. These southern black migrants set their sights primarily on Sierra Leone and Liberia, though others made new homes in other parts of Africa as well. For some of these émigrés, life in Africa amounted to a long sojourn, either as missionaries or merchants. To be sure, many more African Americans nursed dreams of leaving the South or returning to Africa, but family, finances, and fear kept them from joining those who heeded Crummell’s call.

If Africa seemed too distant, costly, and complicated an option for African Americans dissatisfied with Reconstruction policy setbacks, Canada and Mexico became more workable alternatives. It must be recalled that a robust community of African-American expatriates lined the Canadian and Mexican border regions, driven there throughout the nineteenth century by the violence and exploitation of slavery. These émigrés reached the North, Midwest, Canada, Mexico, and various parts of the Caribbean basin through their own designs and sometimes via the Underground Railroad, an oft romanticized network of abolitionists determined to undermine the institution of slavery by funneling freedom seekers out of the South. Whatever the complexities of their new status and the challenges faced by these expatriates in their host countries, the experiment in emigration had sufficiently worked to keep the immigration debate alive—or to revive it once again—with the failure of Reconstruction apparent by 1877.

While some African Americans nourished the hope of a return to Africa, several intellectuals, most notably Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington, remained staunchly opposed to abandoning faith in the full exercise of democracy for African Americans. With slavery abolished, Douglass insisted that the fight for civil rights would require the best of what African Americans had to offer: their labor, their strength, their political resolve, their industry, their economic power, and their commitment to the nation. Even white southerners discouraged emigration to Africa or elsewhere, fearing the loss of the region’s black workforce. The early exodus from the South rattled local whites, who organized bans on black movement through pass systems, convict labor laws, and vigilante bands manning railway depots and riverbanks to prevent African Americans from emigrating under cover of night. Meanwhile, white headhunters found courting black labor for northern coal mines, railway companies, steel mills, meatpacking plants, or other industries were often run out of town or subjected to even fiercer punishment.

Regardless of the threats levied against them, in the late nineteenth century thousands of African Americans ignored Booker T. Washington’s admonition against leaving the South and ran, walked, swam, or boarded trains, cars, and riverboats out of Dixie. Mexico noted a palpable increase in African Americans in its northern states in the late nineteenth century, with many coming from the Texas, Arkansas, and Kansas basin.

Haiti, a country that African Americans held dear since the eighteenth century, became home to many more southern African Americans after 1877, as did other Caribbean islands easily accessible from Louisiana and Florida. But the country that received the greatest requests for admission from southern African Americans in the late nineteenth century was without a doubt the Dominion of Canada, a one-time Promised Land for people on the run from slavers and now Jim Crow.

Canada attracted thousands of African Americans as of the 1880s, in large part because of two timely developments: the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway’s transcontinental rail line, and the federal government’s aggressive homesteading program giving 150 acres of free land to farmers willing to settle in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. African Americans from the South, who were overwhelmingly agricultural workers, turned a gleaming eye toward Canada, where they hoped to make new lives free from the segregationist rule increasingly common in Dixie by the 1890s. Although Canada had embraced runaways, albeit at times reluctantly, by the 1890s many Canadians vehemently opposed black immigration into the West, citing concerns over “inheriting Uncle Sam’s problem.” In letters to their government and in their press, white Canadians denounced African-American migration as a scourge on the nation and a threat to white womanhood. Overwhelmed by the scorn voiced by many white westerners and unable to discourage African Americans from heading to Canada (this despite heavily publicizing Canada’s cold climate in black newspapers), the Canadian government adopted a complete ban on black immigration to Canada in 1911, making African-descended peoples the first ethnic group barred from Canada by federal decree. By the 1920s, Canada would legally bar Chinese, Japanese, and South Asians from its shores as well. Black Americans would continue to find surreptitious ways of entering Canada, and their official numbers peaked at about one thousand per year during the first half of the twentieth century, namely because the Canadian Pacific Railway’s courted them for its sleeping-car service.

American Imperialism and Jim Crow

America’s industrial revolution and the major corporations that it spawned during the Gilded Age (1877–1900) forced an interesting debate on race on an international scale. Effectively, the United States exported two political visions at the end of the nineteenth century that became inextricably linked: white supremacy and American imperialism. Jim Crow, a racialist legal and cultural system predicated on forcibly imposing and violently upholding white rule over people of color, namely African Americans, took shape during the 1890s in the wake of the Mississippi Plan and the enactment of segregation laws in every southern state.

The last decade of the nineteenth century also witnessed American expansion into the Caribbean and Central America, where the United States and American companies declared their divinely inspired design on the regions to their south. With the arrival of Americans, their military, and their corporate interests came demands for more exacting defense of the color line. The interracial workforces made up of whites, Asians, Latin Americans, and African-descended peoples working in Dole’s Central American plantations or on the Panama Canal were racially stratified in a system much like the one American industrial barons imposed back in the United States. On Caribbean islands with American military forces—for example, Puerto Rico, Haiti, the Virgin Islands, and Cuba—there, too, Jim Crow followed soon after armed forces arrived. White American officers bemoaned the freedoms enjoyed by Afro-Cubans, and insisted that restaurants sequester black patrons. For some African-American soldiers in Cuba, their service presented a frustrating paradox. On the one hand, they saw their involvement in the Spanish-American War as an important campaign in making the case for their own meaningful citizenship back home. Yet on the other, they were positioned as a military force sometimes thwarting the advancements of Afro-Cubans.

As the case of African-American soldiers in Cuba illustrates, the turn of the twentieth century, a period historians call the age of imperialism, witnessed an internationalization of Jim Crow thinking and policy that signaled an alarming shift for African- American intellectuals, who saw foreign shores as an important check and balance against American rule. Ida B. Wells, an outspoken journalist, pamphleteer, and civil rights activist, traveled to England in 1893, where she sounded the alarm on lynching’s atrocities. Before large crowds, Wells wedded racial and gender politics, making her case for European support against the epidemic of violence cutting short African American lives, especially those of young black men.

Pan-Africanism

W. E. B. Du Bois, who studied in Germany with renowned sociologist Max Weber, also frequently toured Europe, where he called particular attention to the dehumanizing effect of segregation and white supremacist violence on the lives of African Americans. The Great War weighed heavily on Du Bois’s mind, most importantly because of how it brought the growing tensions over colonialism to light. With his now infamous prediction that the color line would be the greatest problem of the twentieth century, Du Bois understood that the Great War era held enormous promise for advancing the rights of African Americans and other African-descended peoples. In 1919 he forced his way into the League of Nations meeting in Paris in order to voice his concerns over imperialism in Africa. He also traveled extensively in Africa and Asia, where he forged relationships with other intellectuals of color who would later became instrumental during the decolonization movements that lead to independence in South Asia and Africa after World War II. An early Pan-Africanist, Du Bois fundamentally believed in the powerful potential of a coalition of people of color; he spent his life and career fostering international alliances across racial, political, and ideological lines. For this work, Du Bois earned the respect of intellectual-activists both at home and abroad.

Marcus Garvey, the Jamaican-born journalist, entrepreneur, and activist, developed an early awareness of the potential for international alliances among African-descended peoples after working for a time in Central America. Garvey then traveled to England, where he joined forces with West Indians and Africans working mostly in war industries. With the outbreak of World War I, went back to Jamaica and migrated to in New York in 1916, where he established a chapter of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA.) Garvey endeared himself to African Americans by touring the South and seeing how conditions there mirrored those of blacks in the West Indies, Central America, and Europe: in all cases, black people experienced economic, political, and social marginalization, he concluded. Eager to connect with and profit from those Diasporic communities, he published his organization’s newspaper, The Negro World, in French, Spanish, and English and publicized the plights of African-descended peoples from across the Atlantic world.

Garvey emphasized the importance of Africa in the pages of The Negro World, entreating his followers to embrace the continent as their cultural, spiritual, and political beacon. Though he would never visit Africa, Garvey encouraged countless others to do so by selling tickets and shares on his Black Star Line steamship. Once allegations of fraud and financial misconduct stirred members’ ire and drew the attention of the FBI, his movement quickly unraveled. His personal failures notwithstanding, the Pan-African vision that Garvey and his UNIA inspired thrived well into the interwar years (1919–1939), bringing together black intellectual-activists from across the globe for biennial conferences where decolonization efforts put forth their first buds.

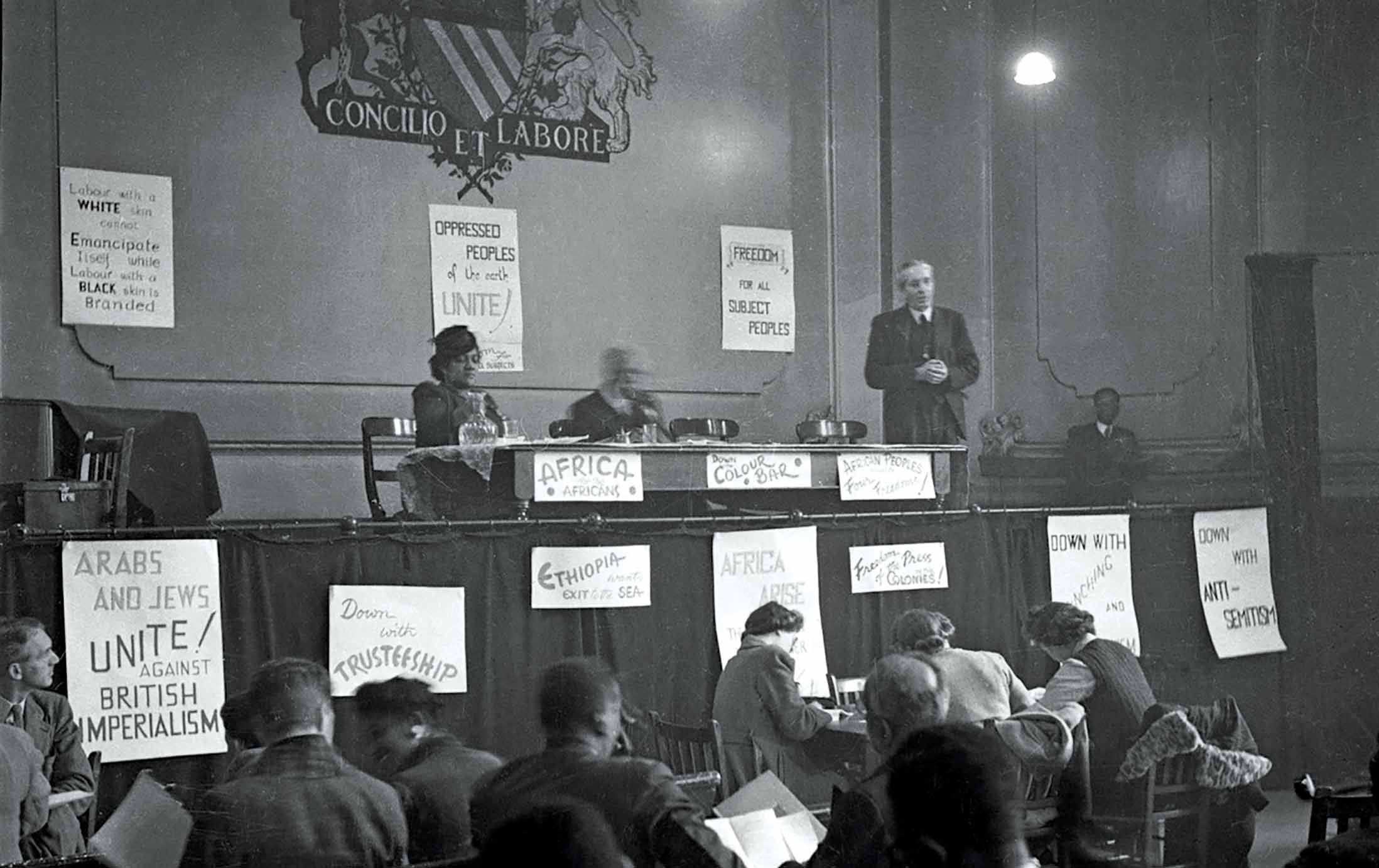

Internationalism

As of the 1920s—but especially after World War II—Pan-Africanists trained their attention on decolonization, the demand for casting off the yoke of imperial rule in Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean. The case of South Africa’s racist regime proved particularly appalling for black intellectual-activists. As early as 1901 W. E. B. Du Bois had warned that during the early twentieth century, the color line he knew so well back in the United States would grow in international appeal. The example of South Africa’s burgeoning apartheid system served as compelling evidence for Du Bois and other like-minded activists. As of the early twentieth century, the United States and South Africa borrowed liberally from each other’s models of white supremacy, exchanging strategies for wresting all forms of political autonomy from blacks. Southerners’ convict labor laws and pass systems proved particularly attractive to South Africans heavily reliant on their captive black workforce. In the end, South Africa and the United States developed into regions deeply committed to violently enforcing their models of white supremacy, earning the scrutiny of black activists across the Atlantic world.

Paul Robeson stands out as the most acclaimed advocate and defender of Africa between the World Wars. Robeson used his draw on the media and his renown to criticize American Jim Crow and South African apartheid, painting both with the same broad stroke. The acclaimed Columbia University lawyer, athlete, actor, and singer never minced words when calling his country to task for violating African Americans’ civil rights. Robeson, who traveled extensively to England, France, Spain, and Germany, explained that he felt most at home in the Soviet Union. There, he told reporters, he could slip the bonds of white supremacy, enjoying real freedom for the first time in his life. Communists applauded Robeson’s undaunted courage, praising him for bringing attention to the freedoms afforded to people of African descent under Soviet rule.

Italy’s violent annexation of Ethiopia during the 1930s deeply troubled Robeson, who called on African Americans to play a greater part in African political matters through the Council on African Affairs, which he created in 1937. Together with Du Bois, who in 1947 published The World and Africa: An Inquiry into the Part Which Africa Has Played in World History, Robeson did more to keep African politics and culture at the forefront of African Americans’ attention, making clear that their fates were connected to those of Africans.

Europeans celebrated Paul Robeson’s politics and his artistic prowess, as well as the black Diasporic culture that he promoted. Europe played host to a broad range of athletes, entertainers, and artists during the interwar years. In London, Paris, and Berlin, African-American soldiers and entertainers set off a jazz craze when they introduced European audiences to the musical form’s spirited improvisational melodies. The list of prominent artists and entertainers who found fame and fortune in Europe is long. Suffice it to say that African Americans whose careers were thwarted by unyielding segregation, as well as anti-miscegenation laws and practices, breathed new life into their careers by going abroad during much of the Jim Crow era, as evidenced by heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson.

Charged with rape under the Mann Act after marrying a white woman, Johnson escaped first to Canada, then Europe, in order to avoid imprisonment or an even worse fate—lynching. Stripped of his license and title, he could not have continued boxing even if he had been able to remain in the United States. In France, where he could fight in interracial matches and earn an even greater income, the bombastic boxer enjoyed a level of freedom unimaginable in most parts of his own country.

Jesse Owens and Joe Louis, undoubtedly the best-known African-American athletes of the interwar era, also earned tremendous praise from European audiences. When asked by awaiting reporters about his reception during the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, Owens soberingly commented that at least in Germany he did not have to ride in the back of the bus, pointing to the paradox faced by so many African Americans abroad. However much they loved and represented their country—whether as soldiers, intellectuals, athletes, or entertainers—once overseas and exposed to a different model of race relations, African Americans often found more acceptance from strangers than their own countrymen. To be sure, few could argue against the fact that by nightfall, a black person was surely safer in Paris, Rio de Janeiro, Toronto, or Bombay than in Macon, Georgia.

The Cultural Front

The popularity of black athletes, entertainers, and artists during the interwar years gave birth to a thriving artistic industry both in Europe and across the Americas. African art inspired postwar European art, most notably the work of Pablo Picasso, its roots at times acknowledged and other times not. Dancers, painters, musicians, and writers in Europe and North America gave shape to their experiences, producing a rich battery of literature and art known in the United States as the Harlem Renaissance and in francophone Africa and the Caribbean as Négritude. That literature and art captured the struggles and challenges of a black Atlantic world. Both artistic movements placed Africa and African culture at their center, with black and white artists at times acting out ostensibly racialized and simplified African stereotypes.

Josephine Baker’s Revue Négre simultaneously celebrated Afrocentricity and her femininity while also exaggerating a distinctly primitive depiction of blackness and specifically Africanness. Parisian Nancy Cunard, of the White Star Line fortune, was perhaps the most active white patron of avant-garde black art in Europe and dedicated her life to codifying that art in her anthology Negro, published in 1934. Back in the United States, African-American artists, who often sharpened their trade during sojourns in Montreal, Paris, Mexico City, London, and Copenhagen, created a rich array of artistic productions that brought to life their transnational experiences, though this aspect of their work is often overlooked by American audiences. For example, Archibald Motley’s acclaimed 1929 painting Blues depicting a steamy speakeasy jazz scene captured Paris’s vibrant, multicultural, and international black world, not New York’s, as is so often presumed. Writer Richard Wright penned some of his most captivating work not in New York but rather in Montreal and Paris, the latter ultimately becoming his home when he grew too disillusioned with Jim Crow’s vice grip on his country.

Jim Crow’s stronghold on American society suffered an important setback after World War II when the full extent of the murderous white supremacy advanced by Germany’s Nazi regime galvanized black intellectual-activists. After the war, African Americans spearheaded the Civil Rights Movement, and West Indians and Africans intensified their demands for independent rule. Desegregation and decolonization were seen as two sides of the same coin: an assault on white supremacist rule. Historian Thomas Borstelmann makes the compelling case that African Americans and other African-descended peoples worked together to bring about major international, social, and political transformations during the Cold War.

Put differently, the partnerships forged between blacks throughout the Diaspora—whether through international organizations like the UNIA, travels, the black press, or military service—formed the foundation for many of the postwar successes. For example, just as W. E. B. Du Bois critiqued the sluggish pace of integration in the United States in the pages of The Crisis, the NAACP publication he edited for decades, he excoriated the slow rate of European decolonization in editorials published in British and French newspapers. In so doing, Du Bois added his voice to those of other political philosophers—such as Aimé Césaire, Léopold Sedar Senghor, C. L. R. James, and George Padmore—who were also working against the culture of white supremacy. In the end, these types of transnational partnerships moved the status of African-descended peoples to the forefront of international politics after 1945, serving, in the process, as powerful catalysts for the political changes sweeping the Atlantic world.

Bibliography

American Colonization Society Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Archer-Straw, Petrine. Negrophilia: Avant-Garde Paris and Black Culture in the 1920s. London: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

Barnes, Kenneth. Journey of Hope: The Back-to-Africa Movement in Arkansas in the Late 1800s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Edwards, Brent Hayes. The Practice of Diaspora: Literature, Translation, and the Rise of Black Internationalism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Gilmore, Glenda. Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919–1950. New York: W. W. Norton, 2007.

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double-Consciousness. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Harris, Joseph, ed. The Global Dimensions of the African Diaspora. Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1993.

Mitchell, Michele. Righteous Propagation: African Americans and the Politics of Racial Destiny After Reconstruction. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Northrup, David. Crosscurrents in the Black Atlantic, 1770–1965: A Brief History with Documents. New York: Bedford-St. Martin’s, 2007.

Okpewho, Isidore, Carole Boyce Davies, and Ali Alamin Mazrui, eds. The African Diaspora: African Origins and New World Identities. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001.

Stovall, Tyler. “The Color Line Behind the Lines: Racial Violence in France During the Great War.” American Historical Review 103 (June 1998).

Winks, Robin W. The Blacks in Canada: A History. 2nd ed. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1997.

Comments

Post a Comment